A few weeks ago, my friend Hendrik Jandel wrote an article about the potential he saw in the Beirut startup scene and how it can become a tech hub in the region. Not surprisingly, his article stirred a lot of debate and opinions about the subject.

Being a tech entrepreneur from the region, I shared my opinion, yet I did it my way (no reference intended).

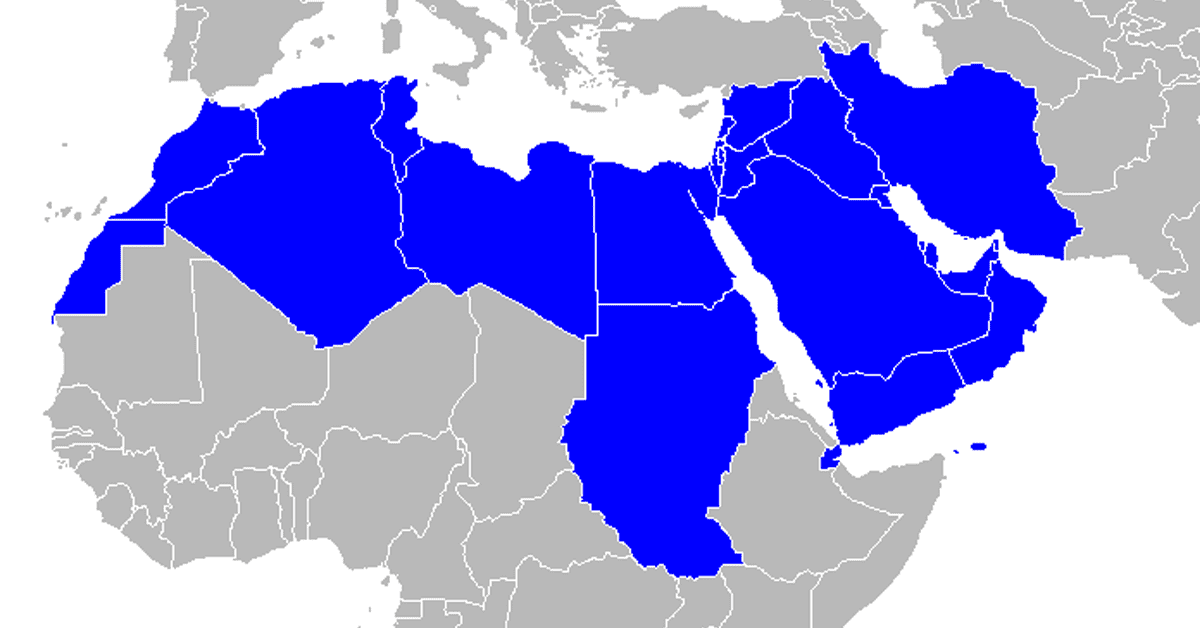

I had a private in-depth discussion with him detailing the logic of how I’ve built my opinion based on my first-hand experience and network in the MENA tech scene.

This article is the summary of my thoughts as discussed with Hendrik after some cleanup and embellishment.

The vibrant tech scene

What would the tech scene in a country/city in the MENA region look like, if it had a strong and vibrant tech sector?

For non MENA people, please note that in this case city and country are quite exchangeable due to the centralized nature of big cities in the region.

This has led me to start defining some quantitative KPIs – to help describe this relative utopic case in a measurable way. Here goes; a vibrant tech city achieving its potential would contain:

- 35-80 revenue making tech companies with healthy unit economics and a total “real” (i.e. post accelerator) valuation of 400-700 million USD.

- A healthy mix of B2B vs. B2C tech companies skewed towards the B2B sector. (I understand this is not quantified, but it doesn’t matter to the assumptions. It will be clear later.)

- An 80/20 split in revenue between local and regional – local being 80%

For the sake of argument and the logical path I’m moving along. I will focus on the 1st point as the underlying line of thought arguing my point.

How would such a tech company look like?

The total valuation of 35 companies at 700 million USD means a 20 million USD valuation each on average. Which means, said companies would have achieved most if not all the following:

- Positive unit economics

- Cash flow positivity

- An aggressive growth trajectory in revenue, traction and/or brand value

- Attracted serious regional and/or international investors

Even at the other end of the scale of 80 companies valued at 400 million USD in total gives an average of 5 million USD valuation per company.

Those numbers still make the case. At least in MENA where the cost of living is inexpensive per international standards, like Cairo or Alexandria (5 million USD ~ 100 million EGP, i.e. a lot of money).

Also, continuing the example: a valuation of 400 million USD is ~8 billion EGP. Which makes the sector comparable to other traditional business sectors in the Egyptian economy. And that’s the lower end of the suggested range.

The higher end of the range is rather applicable to more expensive cities like Amman, Beirut, Dubai, Jeddah, Tunis, etc…

Let’s keep the math simple and work with the following numbers as averages that are to be adjusted per city based on its own dynamics:

- 50 companies

- Total valuation = 500 million USD

- Average company valuation = 10 million USD

How do we get there?

So, how does one reach the above assumed state of startups? Well, assuming VC company success rates of 10% (i.e. 1 out of 10 companies actually succeeds). There needs to be a series A investment in 10 times the above number of companies (i.e. 500 series A investments). This means:

- Series A Ticket size in MENA: 200k USD – 1 million USD

- Total number of investments = 500;

- Total (min) investment = 500 * 200k USD = 100 million USD

So this means that a total of 100 million USD should be invested in series A alone to reach the mentioned state.

We can also calculate it “backwards” to see how much angel/accelerator money is needed to create 500 investible companies ready for series A investment. Also assuming 10 percent hit rate, here are the numbers:

- Angel/accelerator ticket size in Mena: 10k USD – 50k USD

- Total number of angel/accelerator investments = 5000

- Total (min) investment = 5000 * 10k USD = 50 million USD

Although the numbers seem to stack up, let’s put it into perspective:

- Total investment = total accelerator/angel investments + total series A investments = 50 million USD + 100 million USD = 150 million USD

- Total valuation of all “successful” companies post series A = 500 million USD

- ROI = 500 million USD / 150 million USD = 3.33x

Which is a nice ROI in general, albeit not so nice for VCs who expect >10x. But, for jumpstarting an ecosystem into a powerful existence, I would say this is a very good ROI if anyone can achieve it.

One more important factor

Those would be the theoretical numbers that you would find in high-level market studies done by international consultants and VCs.

There is one more aspect that we tend to ignore along with everyone who tries to make reason out of the MENA region’s “special” way of functioning.

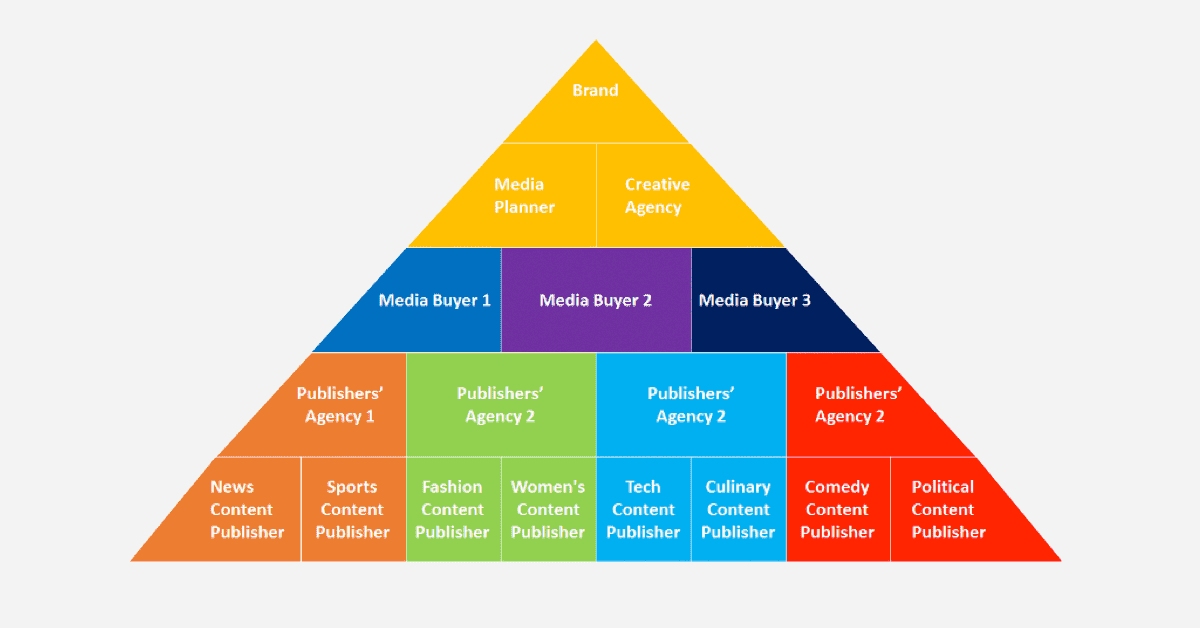

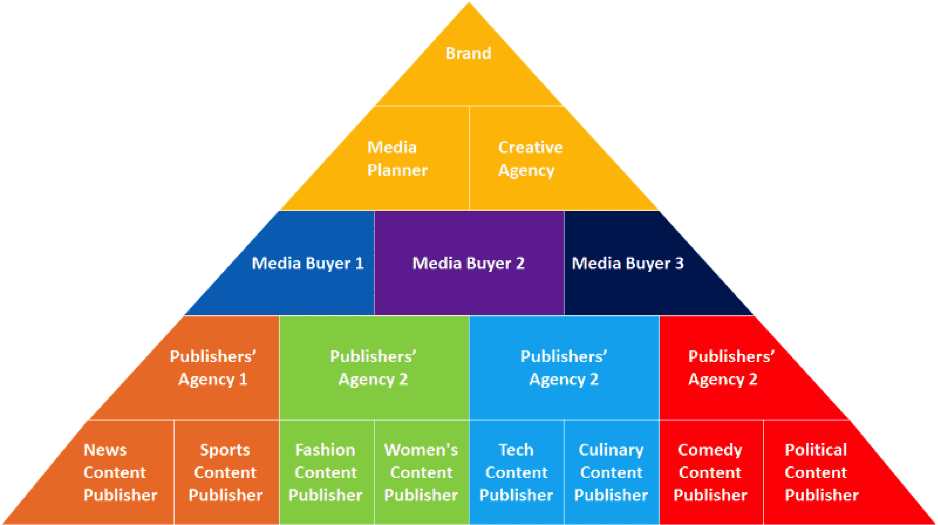

A lot of investors come to the region with “readiness” to risk series A size tickets but claim that there aren’t so many options worth their money or valuations they are asking. Which is to some extent not completely out of this world, though I wouldn’t advocate for it. Yet, here is the situation:

- There are a lot of companies who graduate accelerators seeking series A investments

- Series A investors look for more proven traction (and revenue) than is achievable via accelerator money

- Result = accelerator grads need Series A money to be ready for series A money, i.e. circular references or chicken-egg-problem

What investors call “Series A investible” is not only the state of the company, but also the state of the entrepreneur behind the company.

Before Series A, an entrepreneur isn’t only lacking the money, but also the experience that comes from spending Series A money on growth.

There is a phenomenon I have experienced myself and observed in cases of fellow entrepreneurs. Which I would like to call the post-million-EGP-entrepreneur (this is in 2016 pre-EGP-floating numbers. Feel free to adjust them in your head or via back-of-the-envelope Math).

Spending 1-2 million EGP in Egypt (~50k-100k USD) on building a company opens up some experiences that transform you as an entrepreneur. From an amateur to someone with actual experience (the numbers should now be higher. Also, those numbers don’t apply in more expensive cities, but the concept stands).

This hurdle isn’t surpassable with accelerator money that is designed to be the least possible to enable you to build an MVP and business case on paper. But no real product-market-fit testing or proof of real traction.

Here are some examples of experiences you cannot go through with accelerator money (even if you get creative) and definitely need Series A money for it:

- Proper marketing campaigns to test market response and build acquisition pipelines

- Hiring top talent to lead the company

- Acquiring top tools that help reach product-market-fit

- Be in the market long enough to actually prove market fit

- Make proper mistakes in their first venture that fuel their next venture’s success

- The list can go on…

This also applies to investors

Investors also need to build up their experience and quiet their risk aversion with their money when investing it in series A tickets. This will only happen if they have their own failures behind them. Which lines up quite with the need for building prior experience for entrepreneurs.

We’ve seen lots of inexperienced investors approach the market and of those who have learned from their mistakes as well.

Here are a couple of examples that new investors will only learn if they spend series A money many times:

- Achieving an appropriate and fair level of complexity on the term sheets that doesn’t create bad blood between the shareholders

- Adjust their expectations of market performance and valuations (applies to entrepreneurs too)

- Adjust their speed or slowness of executing an investment deal to the benefit of the company

- Balance their own benefit with the benefit of the company and entrepreneurs and think win-win rather than maximize their gain from the deal and go for win-lose

- This list can also go on…

The market is young on both sides, not only on the investors’ or entrepreneurs’ side. Both sides need to build real experience by trying, spending, failing, learning and adapting.

So, what’s the final tally?

We should add an extra USD 100k per company of the 500 series A investible companies, in order for those 500 entrepreneurs and their investors to throw away the first pancake which will contribute to their next ventures success odds. This brings the tally to:

- Total theoretical investment = 150 million USD

- 500 sunk series A tickets: 500 * 100kUSD = 50 million USD

- Total investment = 150 million USD + 50 million USD = 200 million USD

- Total ROI = 500 million USD / 200 million USD = 2.5x

2.5x is still good ROI in my view, although I know that VCs would differ.

Reality check: How & Who?

The next question would be: how can this be done and who could/should do it?

Concrete answer: I don’t know exactly. I’m not a finance guy. But, here would be my general thoughts:

- The money needs to come from a source that is OK with the 2.5x and a probability of less return, but with a longer-term focus.

- It could be a combination of International Institutions, VCs, International Funds, Angel funds, Governments…. Don’t know exactly how though.

- The money needs to be spent even though chances of corruption or at the very least misspending would be relatively high. This is a given factor in this journey and it is there by design. Thus, some level of due diligence is needed, but there should be high awareness to avoid overkill in such processes.

- It also doesn’t need to happen all at once. It could be phased but with the awareness that each phase on its own is only building up to the end-goal. Lots of lean and agile principles can be applied in the actual execution strategy to reach the above goals of spending and 35-80 strong tech companies of a total valuation upwards of 700 million USD.

- Then money on its own is not the solution. There are some other factors that contribute to the success and/or failure of the ecosystem. But the money catalyzes the effect of everything else. If it is not there, all other factors have very limited effect.

Finally…

All the above are my thoughts, ideas and opinions. I am happy to discuss them and to have a meaningful debate around them to challenge them or discuss them in further depth and details.